Conway's Law

Many organizations have become adept at identifying what they need from software development projects, based on a keen understanding of their business goals. Even so, they’re often surprised to find out that the end results don’t achieve the transformative impact they were expecting. Their mistake? Overlooking the importance of Conway’s Law.

In 1967, Melvin Conway coined a phrase at the end of his publication ‘How do committees invent?’ that was subsequently made popular by Fred Brooks in his book The Mythical Man-Month, where he dubbed it ‘Conway’s Law’, which states:

Organizations which design systems are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations - Conway, 1967.

Although this is not a scientific law, it is a valid proposition for many environments. We often see its effects in our workplace and in other companies that develop software. Organizational structure reflected in systems So what does this mean in practice? What happens when organizational structure is reflected in the systems it produces? Well, take an invoicing department: that means there’ll be an invoicing system for sure; if there are a notifications areas, there’ll be notification systems; the finance department has a finance system, and so on. These systems will integrate with each other in a way that mirrors the way these organizational departments communicate.

Conway’s Law also plays a role in the time it takes to construct each of these systems. That’s because the architecture of these products will reflect the communication structure of the teams that are part of that process.

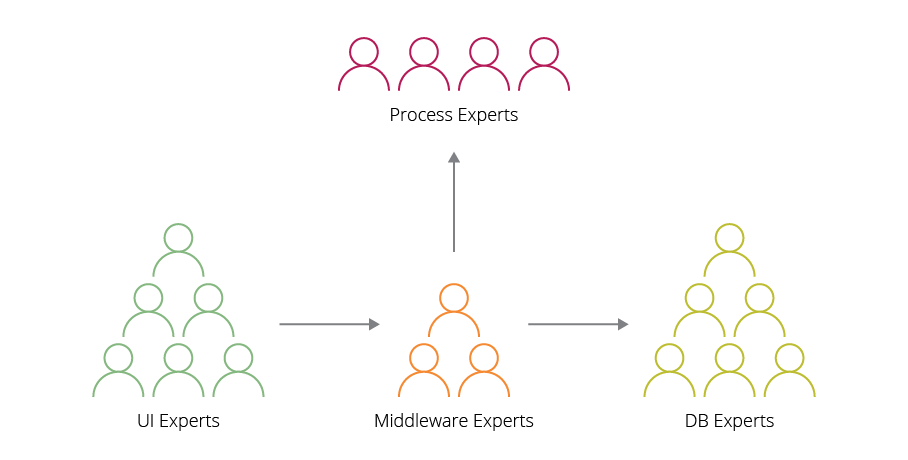

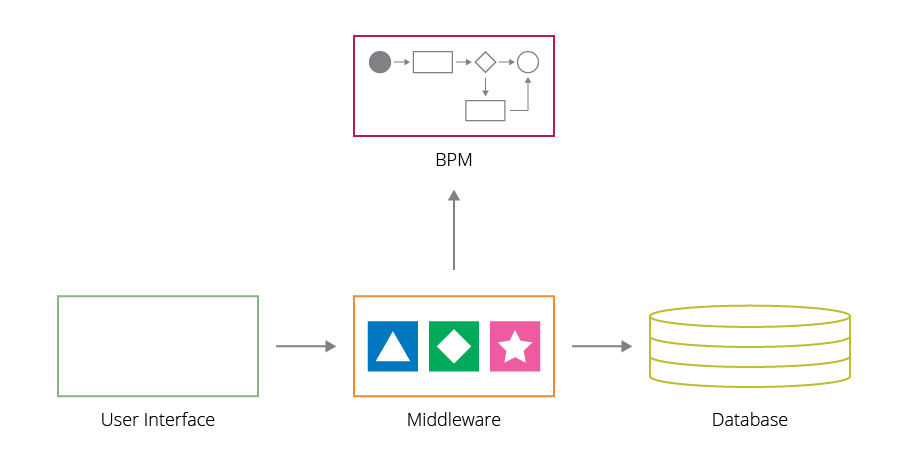

As a result, if the technology department is organized around technical capabilities, with a work group focused on the user interface, another group to the database, a third to the infrastructure, one to the process management, another to the implementation of business logic on the server side (figure 1), the architecture of the resulting systems (figure 2) will be very similar to these communication structures.

Figure 1: Technical organization of teams

Figure 2: Architecture driven by technical capabilities

Systems are dynamic, there will always be changes, and these are often caused by changes to the business definitions. If an organizational structure is driven by technical capabilities, every change in the business definitions will require work from all the technical areas of the organization, budget and time assignment.

This is one of the reasons why some organizations try to group requirements to ‘optimize’ time and resources, lengthening the development process until all the necessary work can be ‘justified’. Often, the end result is just dissatisfaction with the technology department.

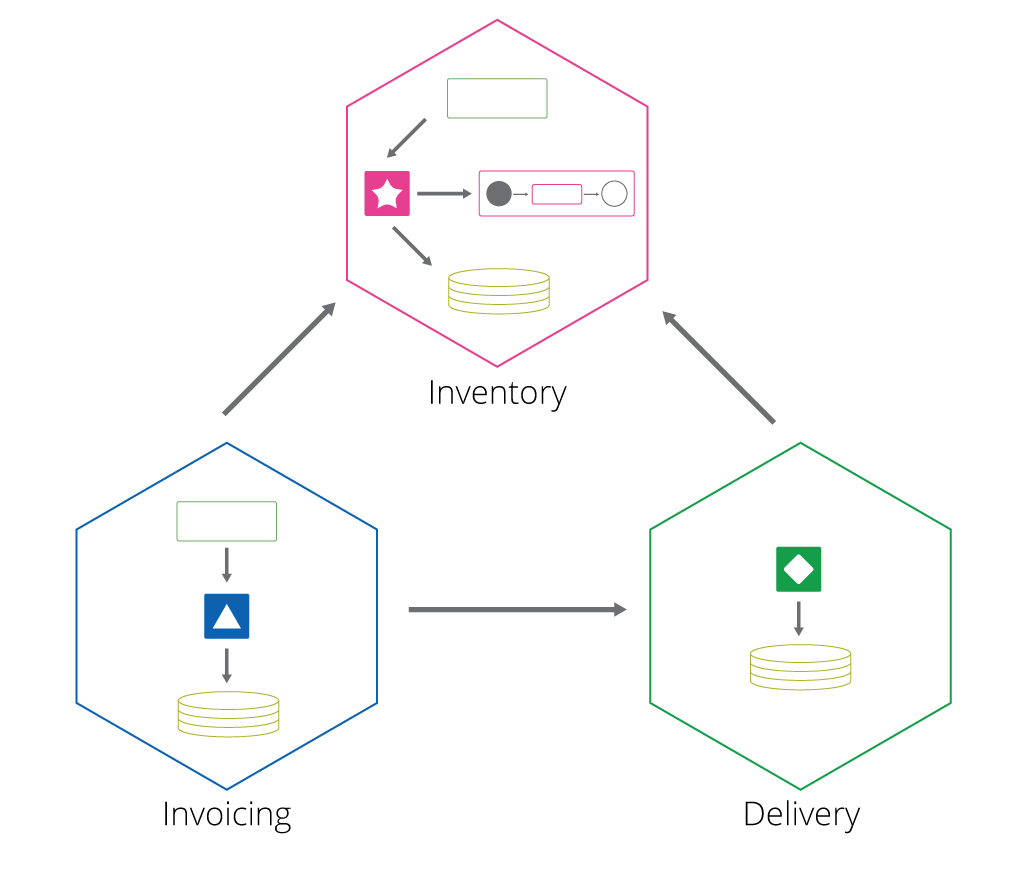

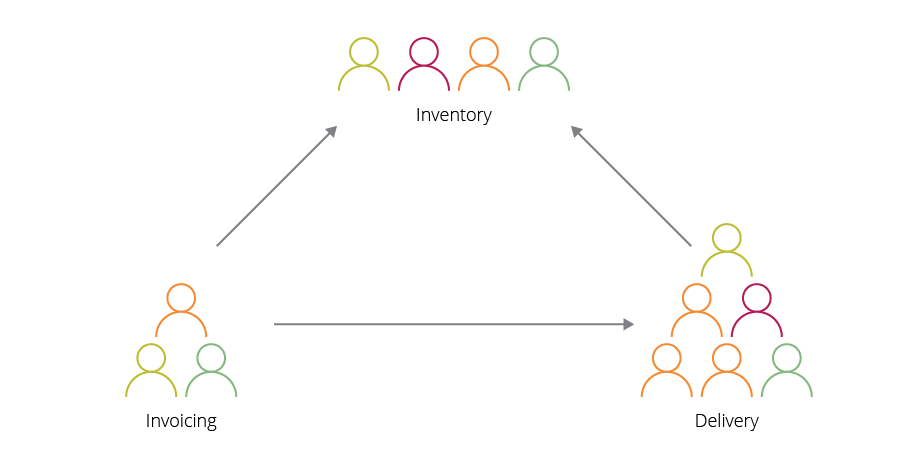

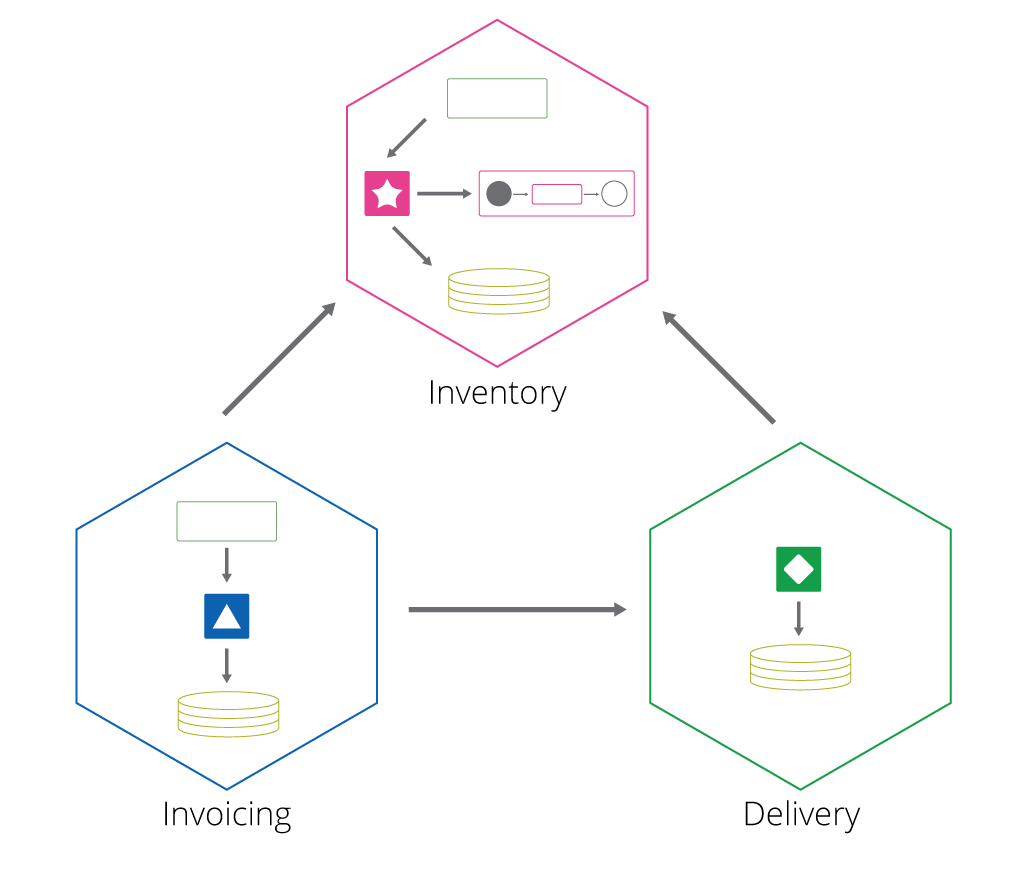

On the other hand, we can find organizations that favor multidisciplinary or cross-functional teams formed by different roles and guided by the business capabilities (figure 3). Here, changes produced by new business definitions are executed from beginning to end by just one team. This avoids processes overhead, and produces different—and often more distributed—architectures (figure 4) with greater capacity to evolve. Organization of teams driven by business capabilities

Figure 3: Organization of teams driven by business capabilities

Figure 4: Business-driven architecture

In the end, software is the product of an intellectual and collaborative process that will reflect the ideas of the people involved in this process and the communication structures between teams. That means, accounting for Conway’s Law should be front of mind, when it comes to structuring teams.

Organizations have different needs in terms of software architecture and usually they know what is the expected architecture that will allow them to achieve their business goals. However, they forget the implications of people structure, what we can learn here is that we need to set up our teams aligned with the architecture we are expecting.